Handy Links

SLAC News Center

SLAC Today

- Subscribe

- Archives: Feb 2006-May 20, 2011

- Archives: May 23, 2011 and later

- Submit Feedback or Story Ideas

- About SLAC Today

SLAC News

Lab News

- Interactions

- Lightsources.org

- ILC NewsLine

- Int'l Science Grid This Week

- Fermilab Today

- Berkeley Lab News

- @brookhaven TODAY

- DOE Pulse

- CERN Courier

- DESY inForm

- US / LHC

SLAC Links

- Emergency

- Safety

- Policy Repository

- Site Entry Form

- Site Maps

- M & O Review

- Computing Status & Calendar

- SLAC Colloquium

- SLACspeak

- SLACspace

- SLAC Logo

- Café Menu

- Flea Market

- Web E-mail

- Marguerite Shuttle

- Discount Commuter Passes

-

Award Reporting Form

- SPIRES

- SciDoc

- Activity Groups

- Library

Stanford

Around the Bay

Researchers Trace the Origin of Super-massive Black Holes

In the very early universe, soon after the first stars formed, black holes more massive than a billion Suns already speckled the sky. For years, these super-massive black holes were a cosmic anachronism. Although cosmologists put forth two theories for how they might have formed, neither offered a satisfying explanation for how these behemoths came into existence less than a billion years after the Big Bang. Now, in a paper published today in Nature, a team of researchers describe a third theory.

"Putting together a viable model for the origin of these super-massive black holes is a difficult theoretical task," said Stelios Kazantzidis, a former researcher at the SLAC/Stanford Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology who now works at The Ohio State University's Center for Cosmology and Astro-Particle Physics. "Yet we know from observations that super-massive black holes existed very early on in the history of the universe."

To explain these observations, astrophysicists had previously suggested that small "seed" black holes born in the collapse of the first stars could have quickly grown enormous by pulling in nearby gas or merging with other small black holes. Yet recent analysis suggests there just wasn't enough gas near these seeds for them to grow fast enough to explain observations. Alternatively, researchers have suggested that the gas in a forming galaxy—called a "protogalaxy"—could have spontaneously collapsed to form a large black hole. Yet this theory requires idealized conditions in which the gas is extraordinarily dense and metal-free.

Working with two researchers from the University of Zürich, Kazantzidis and then-KIPAC researcher Andres Escala sought to find a more reasonable explanation. The researchers posited that if two protogalaxies were to merge, together they might create a gas cloud massive and dense enough to collapse into a substantial black hole.

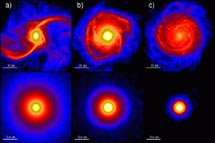

To test this theory, the researchers created the most detailed simulations to date of two identical protogalaxies merging. Each galaxy consisted of a massive and extended dark matter halo surrounding a disk of stars and gas.

In the simulations, the merging protogalaxies orbit one another until gravity pulls them close enough to collide, producing a very dense but turbulent region. Like water down a drain, the gas in the nascent galaxies travels with great speed—several hundred kilometers per second—as it spirals toward the center. Yet unlike water in a drain, the matter has nowhere to go once it reaches the middle of the merged galaxies. As more and more gas squeezes into this small central region, an incredibly dense cloud forms. About 100,000 years after the two protogalaxies merge, the cloud becomes too massive to support its own weight and begins to collapse in on itself—creating just the right conditions for a super-massive black hole to form.

At this point in the simulation, just as all is about to be revealed, the scene goes fuzzy. Although the simulations offer higher resolution than any before—indeed, they took an impressive half a million CPU hours to run on supercomputers at the University of Zürich and the Ohio State Supercomputer Center—the resolution is not quite high enough to show the cloud's collapse, becoming too coarse at this point to be useful.

Nonetheless, this work reveals for the first time that mergers between protogalaxies are likely to have led to the direct formation of super-massive black holes in the very early universe. "Here we found a third route by which super-massive black holes can form," said Escala, who is now at the University of Chile. "Because galaxy mergers are a fairly common occurrence in the universe, this is a route that's likely to happen from normal conditions."

As computing power advances, the researchers will be able to repeat these simulations with better resolution and more detailed physics. In the meantime, Kazantzidis said, they will focus on refining the simulations' initial conditions to include many types of protogalaxies, not just identical ones, and improving the accuracy of physical effects in the simulation. In this way, the researchers hope to generalize the applicability of their model and shed light into the co-evolution of galaxies and super-massive black holes in the early universe.

This work, published this week in Nature, was conducted by L. Mayer of the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Zürich; S. Kazantzidis of the Center for Cosmology and Astro-Particle Physics and the departments of Physics and Astronomy at The Ohio State University; A. Escala of the department of Astronomy at the University of Chile and SLAC's Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology; and S. Callegari of the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Zürich.

—Kelen Tuttle

SLAC Today, August 26, 2010