Handy Links

SLAC News Center

SLAC Today

- Subscribe

- Archives: Feb 2006-May 20, 2011

- Archives: May 23, 2011 and later

- Submit Feedback or Story Ideas

- About SLAC Today

SLAC News

Lab News

- Interactions

- Lightsources.org

- ILC NewsLine

- Int'l Science Grid This Week

- Fermilab Today

- Berkeley Lab News

- @brookhaven TODAY

- DOE Pulse

- CERN Courier

- DESY inForm

- US / LHC

SLAC Links

- Emergency

- Safety

- Policy Repository

- Site Entry Form

- Site Maps

- M & O Review

- Computing Status & Calendar

- SLAC Colloquium

- SLACspeak

- SLACspace

- SLAC Logo

- Café Menu

- Flea Market

- Web E-mail

- Marguerite Shuttle

- Discount Commuter Passes

-

Award Reporting Form

- SPIRES

- SciDoc

- Activity Groups

- Library

Stanford

Around the Bay

Researchers Reconstruct Complete Protein Network

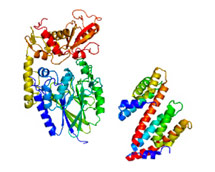

Researchers at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource have helped resolve the structures of 73 proteins involved in the metabolic processes of Thermotoga maritima, a heat-loving bacterium found in deep-sea thermal vents. The work is part of a larger study conducted by the Joint Center for Structural Genomics and collaborators to reconstruct the organism's central metabolic network—a complex system that encompasses more than 478 different proteins. Published in the September 18 issue of Science, the study is the most comprehensive of its kind ever completed. The results could help explain how metabolic networks evolve, and could help drive further research in both medicine and energy science.

After screening the samples, researchers used the SSRL protein crystallography beam to create X-ray diffraction patterns of the crystallized proteins. Analyzing the patterns, they were able to determine each protein's three-dimensional structure. Researchers at the Burnham Institute for Medical Research then combined the SSRL data with 358 protein structures determined using computer modeling techniques, creating a map of how the different proteins interact with other molecules.

"We have complete coverage for all the pathways that perform all of the organism's essential functions," said SSRL Senior Staff Scientist Ashley Deacon, core leader for the JCSG Structure Determination Core.

The study, part of an ongoing project to examine the structure of T. maritima proteins, was a combined effort of several JCSG member institutions. First, researchers at the JCSG bioinformatics group at University of California, San Diego, chose the proteins to be studied. Researchers at the JCSG crystallomics group at the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation in San Diego then prepared the protein crystals for analysis by the JCSG Structure Determination Core at SSRL.

For scientists at SSRL, this study meant screening 800 T. maritima samples over the course of 10 years. According to Deacon, the automated capabilities of SSRL's Beamline 1-5 were crucial in processing the enormous sample set.

"For a high throughput project like this, the automation really helps out," Deacon said. "We don't have to be there to screen the samples. We have robots on the beamline that can put them in place."

While the biochemical steps of many metabolic processes have been long understood, researchers have only relatively recently been able to consider the three-dimensional structures of the proteins involved. According Burnham Institute for Medical Research physicist Adam Godzik, who was the lead investigator on the study, being able to study structure opens a whole new level of understanding.

"Knowing the structure gives you a picture of what's really happening," Godzik said. Aside from biochemistry, knowing the structure also gives researchers an eye to evolution. "It gives you a deeper view into history. When you look at sequences, things might have evolved so much that you cannot see the similarity any more. Structure is much more conserved."

In addition to giving researchers a clearer idea of how the different proteins in the network interact, the results could allow researchers to build computer simulations to determine how cells might respond to novel compounds such as pathogens or pharmacological agents. And because T. maritima produces hydrogen and oil-like substances as metabolic byproducts, the results could also help drive energy research. According to Godzik, several ongoing studies funded by the Department of Energy are looking for ways that the organism's metabolic network could be tweaked to boost production of energy-rich substances for use as fuel.

Over the coming months and years, researchers at SSRL will continue working to figure out more of T. maritima's protein structures.

"We're constantly going back and trying to solve structures that we couldn't solve initially," Deacon said.

The study was funded by the Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medicine Sciences.

—Nicholas Bock

SLAC Today, October 13, 2009