Handy Links

SLAC News Center

SLAC Today

- Subscribe

- Archives: Feb 2006-May 20, 2011

- Archives: May 23, 2011 and later

- Submit Feedback or Story Ideas

- About SLAC Today

SLAC News

Lab News

- Interactions

- Lightsources.org

- ILC NewsLine

- Int'l Science Grid This Week

- Fermilab Today

- Berkeley Lab News

- @brookhaven TODAY

- DOE Pulse

- CERN Courier

- DESY inForm

- US / LHC

SLAC Links

- Emergency

- Safety

- Policy Repository

- Site Entry Form

- Site Maps

- M & O Review

- Computing Status & Calendar

- SLAC Colloquium

- SLACspeak

- SLACspace

- SLAC Logo

- Café Menu

- Flea Market

- Web E-mail

- Marguerite Shuttle

- Discount Commuter Passes

-

Award Reporting Form

- SPIRES

- SciDoc

- Activity Groups

- Library

Stanford

Around the Bay

The LHC and the Hunt for Hidden Dimensions

In a talk at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute last Wednesday, SLAC physicist JoAnne Hewett explained how the Large Hadron Collider can solve a puzzle that has vexed physicists for more than a century: the proposed existence of extra dimensions.

Describing the exact location of Hewett's talk requires reference to the four dimensions that people experience: three spatial dimensions (to locate the SETI Institute in Mountain View, CA), and time (Wednesday, February 5). Theoretical physicists suggest that the universe includes up to six or seven additional dimensions too small to be observed. Finding evidence of these phantom dimensions would solve several of the biggest problems in modern physics, notably showing that all fundamental forces can be combined into one, and possibly providing evidence for string theory.

Unification, the idea of combining many forces into a single force, was first addressed in the 1860s when James Clerk Maxwell showed that electricity and magnetism were part of the same interaction, the electromagnetic force. Electricity can produce magnetic fields, and magnets can produce electric fields. In 1919 a mathematician named Theodor Kaluza suggested that Einstein's theory of gravity could be paired with the electromagnetic force into a single consistent theory if there were an invisible fifth dimension.

"This is the first instance in which scientists used an extra dimension to solve a physical problem: to unify the two fundamental forces that existed in nature that they knew about at that time," Hewett said.

A century after Maxwell, physicists showed that the electromagnetic force and the weak nuclear force were also part of the same interaction, dubbed the electroweak force. Now researchers are trying to tie in two more forces, the strong nuclear force and gravity. One way to do this is, Hewett said, is with string theory.

String theory says that matter can be broken down beyond electrons and quarks into miniscule loops of string. The strings move and vibrate at different frequencies, giving particles the properties we observe, like mass and charge. String theory can unite all four fundamental forces and explain the origin of all of the fundamental particles in the universe—but only if there are six or seven more dimensions, billions of times smaller than anything visible with the most powerful microscopes on earth.

"String theory doesn't make sense unless you have extra dimensions of space," Hewett said.

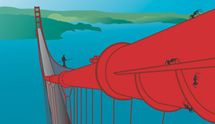

These extra dimensions are "curled up and compact," hiding within the dimensions we interact with every day, she said. She explained this by asking the audience to imagine a tightrope walker teetering on a cable above the Golden Gate Bridge. The tightrope walker sees only one dimension, oriented forward and back. But a colony of ants crawling on the same cable sees another dimension: the cable's circumference. What looks like two dimensions to the ants looks like one to the tightrope walker. Similarly, space could look like it only has three dimensions to us, but nine or ten dimensions to a tiny vibrating string. "All we have to do is find them," she said.

There are two ways to search for the footprints of extra dimensions, Hewett said. The first is to take careful measurements of gravity at very short distances. If gravity leaks into extra dimensions, as some physicists propose, the equation describing how gravity works would be different at tiny distances than at large distances. Unfortunately, the best measurements possible at the moment haven't revealed any difference.

Supernovas provide a second method of dimension hunting. When stars burn up their fuel and explode, they expel particles and massive amounts of energy. They could create an exotic particle called a graviton that zips off into another spatial dimension as soon as it forms, taking some energy with it. If researchers knew how much energy went into the supernova explosion, they could compare it to the amount of energy left afterward. If some energy were missing, it would be evidence for extra dimensions. But knowing precisely how much energy goes into the explosion is almost impossible.

The LHC will get around this problem, Hewett said. The collider will make explosions that are like supernovas in a microcosm. Physicists will know how much energy goes into each collision and how much comes out, so they will be able to tell whether it produced gravitons. "We don't see the graviton itself, because it just flies off into the other dimension," Hewett said. "What we can see is the energy that it carries away."

Hewett says she finds it most exciting that the shape of space-time can reveal so much about the universe. "For me it's not new particles, not a new equation," she said. "It's the actual geometry of space-time."

You can watch Hewett's talk on the SETI Institute's Web site.

—Lisa Grossman

SLAC Today, February 12, 2009