Handy Links

SLAC News Center

SLAC Today

- Subscribe

- Archives: Feb 2006-May 20, 2011

- Archives: May 23, 2011 and later

- Submit Feedback or Story Ideas

- About SLAC Today

SLAC News

Lab News

- Interactions

- Lightsources.org

- ILC NewsLine

- Int'l Science Grid This Week

- Fermilab Today

- Berkeley Lab News

- @brookhaven TODAY

- DOE Pulse

- CERN Courier

- DESY inForm

- US / LHC

SLAC Links

- Emergency

- Safety

- Policy Repository

- Site Entry Form

- Site Maps

- M & O Review

- Computing Status & Calendar

- SLAC Colloquium

- SLACspeak

- SLACspace

- SLAC Logo

- Café Menu

- Flea Market

- Web E-mail

- Marguerite Shuttle

- Discount Commuter Passes

-

Award Reporting Form

- SPIRES

- SciDoc

- Activity Groups

- Library

Stanford

Around the Bay

KIPAC Workshop Looks Back in Time to Understand the Universe

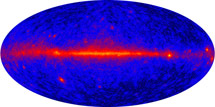

When astronomers look to the sky, they see millions upon millions of individual objects: the discernable stars and other sources of light that make up our universe. But they also see a faint, diffuse glow spread across the entire sky that can't be attributed to single sources. This light, which consists mostly of the light from galaxies and quasars too far away to individually resolve, was the subject of the Cosmological Implications of the Extragalactic Background Light workshop that took place at SLAC on Tuesday.

"After you subtract all of the point sources from your view of the sky, the extragalactic background light is what's left," said Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology postdoc Lukasz Stawarz, who co-organized the workshop with colleagues Neelima Sehgal and Jack Singal. In addition to the blurred light of distant astronomical objects, the EBL also includes the cosmic microwave background, a faintly glowing relic of the hot, dense, young universe. Together, these sources contain information regarding the history and formation of galaxies, and the large-scale structure of the universe.

Researchers have studied the extragalactic background light for decades, but only recently have advanced telescopes, satellites—such as the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope—and even balloon-borne instruments allowed them to view it at a wide range of wavelengths including X-ray, radio, infrared and optical light.

"For a long time, people who studied one wavelength would work closely with others who studied the same wavelength," said Sehgal. "This workshop is one of the first to bring together people who study all the different wavelengths. By working together, we can get a holistic picture of the universe."

Researchers like Sehgal hope that by working together, they will better understand the structure of the early universe, and how that structure has evolved over time. Because it takes time for light to travel great distances across the universe, when researchers look at objects very far away, they are looking back in time, seeing the light that these objects emitted millions of years ago. Even if they can't resolve individual sources, they can learn much about the early universe from the aggregate light. Because different mechanisms produce the light in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, studying the EBL in many wavelength bands probes a variety of processes in the universe. By studying the aggregate EBL in many different wavelengths, researchers seek to learn how the structure of the early universe evolved over time.

Observations of the EBL also may reveal insights into new physics, including dark matter and dark energy. While most dark matter searches focus on specific areas of the sky where theories suggest dark matter will clump, the EBL offers researchers the opportunity to look for the evidence of dark matter particles spread out across the entire universe. Likewise, researchers hope that by better understanding how structure evolved in the universe over time, they will better understand the dark energy thought to increase the speed at which the universe—and everything in it—is expanding.

"Since the EBL encodes so much information about the universe, it was great to get all of these researchers together to exchange ideas," said Singal. Tuesday's workshop, which brought together about 25 local researchers from KIPAC, UC Santa Cruz and UC Berkeley, was so successful, Singal said, that he is already looking forward to having such an event again.

—Kelen Tuttle

SLAC Today, December 17, 2009