Handy Links

SLAC News Center

SLAC Today

- Subscribe

- Archives: Feb 2006-May 20, 2011

- Archives: May 23, 2011 and later

- Submit Feedback or Story Ideas

- About SLAC Today

SLAC News

Lab News

- Interactions

- Lightsources.org

- ILC NewsLine

- Int'l Science Grid This Week

- Fermilab Today

- Berkeley Lab News

- @brookhaven TODAY

- DOE Pulse

- CERN Courier

- DESY inForm

- US / LHC

SLAC Links

- Emergency

- Safety

- Policy Repository

- Site Entry Form

- Site Maps

- M & O Review

- Computing Status & Calendar

- SLAC Colloquium

- SLACspeak

- SLACspace

- SLAC Logo

- Café Menu

- Flea Market

- Web E-mail

- Marguerite Shuttle

- Discount Commuter Passes

-

Award Reporting Form

- SPIRES

- SciDoc

- Activity Groups

- Library

Stanford

Around the Bay

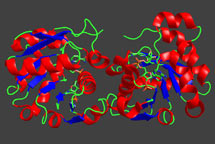

Biology—Now in 3-D!

Consider the structure of a protein, solved by users at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource. Some proteins have deep crevices or appendages that pivot and rotate. But scientific papers by necessity present these dynamic three-dimensional structures with flat and static two-dimensional pictures. Biologists can now share 3-D images of their proteins with simple Portable Document Format files.

"So much of what we do in science is 3-D information, especially at SSRL," said SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory physicist Norman Graf. "[SSRL scientists'] whole point is to find information in 3-D."

In his own work, Graf uses PDF files to share 3-D schematics of particle detector designs. But after he read about the structure of a protein called Steap3, which was solved using SSRL's Beamline 9-2, he was curious to see the protein in its true 3-D shape.

He only needed two pieces of software. With the help of Montana State University researcher Martin Lawrence, who helped solve the Steap3 structure, Graf found the first piece—a free program called PyMOL that allows biologists to study 3-D protein structures. The other piece was the newest version of Adobe Acrobat, which creates PDF files. Once both programs were running, Graf hit a single button and Acrobat grabbed the 3-D data for the protein and pasted it into a file.

"It's magic," Graf said.

Users viewing the image can spin the protein and inspect it from different perspectives. They can zoom into specific regions to get more detail. The creator of the file can also produce animations of the protein to show it in pre-defined orientations highlighting areas of interest.

PDF files have supported 3-D images for a few years, but they've been used mainly for 3-D engineering designs. Graf said he believes PDF files are ideal for sharing 3-D scientific data, because these files are the standard in electronic publishing. They can be viewed using a free program called Adobe Reader, which can run on Windows, Linux or Mac operating systems. Also, Acrobat can grab information from any scientific software that uses the OpenGL (Open Graphics Library) industry standard format to display 3-D graphics.

In October, Graf presented a talk on how to use PDF files to display high-energy physics data in three dimensions at the Nuclear Science Symposium sponsored by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

"If you're into outreach, communication or education and need to work across multiple platforms, this will allow you to interact," Graf said.

Montana State scientist Lawrence said researchers in the biology community are discussing how to use this technology to display protein structures in the electronic versions of research articles. Robert Simoni, who is a professor of biology at Stanford University and the deputy editor of the Journal of Biological Chemistry, says his journal has begun encouraging authors to submit 3-D images in their PDF files. Astronomers are also considering 3-D content in their research papers, as noted in a recent New Astronomy article, and using 3-D in various formats to visualize space. (For an example using 3-D animation, see "Flight to the Virgo Cluster.")

"I think that scientists are definitely interested in embedding these 3-D images into their publications," Lawrence said. "As the ability to do this becomes better known, it will become quite common."

ŚMichael Torrice

SLAC Today, November 20, 2008