Handy Links

SLAC News Center

SLAC Today

- Subscribe

- Archives: Feb 2006-May 20, 2011

- Archives: May 23, 2011 and later

- Submit Feedback or Story Ideas

- About SLAC Today

SLAC News

Lab News

- Interactions

- Lightsources.org

- ILC NewsLine

- Int'l Science Grid This Week

- Fermilab Today

- Berkeley Lab News

- @brookhaven TODAY

- DOE Pulse

- CERN Courier

- DESY inForm

- US / LHC

SLAC Links

- Emergency

- Safety

- Policy Repository

- Site Entry Form

- Site Maps

- M & O Review

- Computing Status & Calendar

- SLAC Colloquium

- SLACspeak

- SLACspace

- SLAC Logo

- Café Menu

- Flea Market

- Web E-mail

- Marguerite Shuttle

- Discount Commuter Passes

-

Award Reporting Form

- SPIRES

- SciDoc

- Activity Groups

- Library

Stanford

Around the Bay

SLAC at the LHC: The ATLAS High-Level Trigger

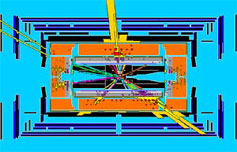

When the Large Hadron Collider proton beams smash head-on inside the ATLAS detector, the great majority of the results will involve physics we already know. And that's a good thing. The LHC proton beams will cross about 40 million times every second, and recording each collision requires so many gigabytes of data that researchers can save only about 200 collisions per second. To whittle down this huge amount of data without losing the good bits, ATLAS uses what's called a trigger system. Its job is to quickly determine which collisions show new, unexplored physics and which do not. SLAC researchers are working on several aspects of the trigger, including a system that ensures its quick decisions are based on the best information possible, and another that helps the trigger's many computers work independently.

"The trigger code must deliver the optimal answer and do it very fast," said Su Dong, who co-leads the SLAC ATLAS team with SLAC physicist Charlie Young. "We're working to come up with various ways to help make this possible."

In order to ignore as many "boring" events as possible while not accidentally discarding the interesting ones, the trigger system processes the data in several steps. It first makes a very quick and cursory comparison between each detected event and expected signatures of new, interesting events. Using custom-built fast electronics, this "Level 1" step takes about 3 microseconds to reject events that clearly don't match any of the signatures. This reduces the 40 million collisions recorded each second to about 100,000 potentially interesting collisions per second. Then, with fewer collisions to consider, the Level 2 trigger can spend a little more time—about 40 milliseconds—analyzing each event. Using a farm of up to 500 computers, it conducts a second round of analysis, searching for subtle characteristics that may indicate new or particularly interesting physics. Finally, a farm of up to 1600 computers carefully analyzes the most promising events and permanently records approximately 200 of them per second for later study.

Su served for many years as the system manager for the BaBar detector trigger system along with SLAC physicist Rainer Bartoldus. Together, Su, Bartoldus and graduate student David Miller are now applying the expertise they gained on previous experiments to create a real-time beam spot monitoring system. The system will ensure the data used by the ATLAS trigger has a precise reference point. It uses the pixel detector to monitor the LHC proton beam interaction region size and location, which may vary with time. This information helps to ensure that decisions made by the trigger system are based on the most accurate and precise data possible. These measurements will also provide important information for tuning the accelerator.

"This system not only needs to give feedback as quickly as possible, it needs to give feedback to itself, and that's what makes it challenging," said Bartoldus, who heads the SLAC trigger and data acquisition group. "There's no hindsight. The trigger needs to determine where the beam is by gathering information from its thousands of processes, finding out if it has moved, and feeding this back to the thousands of processes in real time, so the new beamspot can be used for triggering the next events."

To set itself up at the start of every run, each of the trigger processes needs to receive tens of megabytes of configuration data from an online database. Letting all processes talk to the database directly at the same time would create chaos and delays of up to an hour. To combat this, SLAC researcher Andrei Salnikov, working with Sarah Demers, Amedeo Perazzo and Bartoldus, created a proxy system through which the trigger computing farm's 2000 computers—and their 16,000 simultaneous processes—interact with the database in an orderly way. This provides a hierarchical network for the distribution of database information and reduces the configuration time to less than a minute. Configuration of the entire farm is done in parallel, in the time it takes to configure a single machine.

The bulk of the trigger algorithm work seeks to strike a very careful balance between discarding uninteresting events and keeping all potentially interesting ones. This work is especially complex because it must take into account events that demonstrate new physics and therefore may have surprising signatures. The strategy is to build the decision based on some basic categories of signatures. SLAC postdoctoral researchers Demers and Ignacio Aracena have been working on the high level trigger algorithms involving tau leptons, hadronic jets and missing energy. Ariel Schwartzman, an assistant professor at SLAC, has worked on the Level-2 b-quark tagging trigger.

Trigger algorithms often rely on the signatures of interesting events. To know which signatures are the most important to retain, researchers need to first determine what theoretical physical processes would look like as seen through the detector. To do this, they would like to simulate thousands of events—which takes a significant amount of time at an average of 15 minutes apiece. To help increase the speed of simulations, researchers in the SLAC experimental group, including Makoto Asai and Dennis Wright, have created a program that monitors where time is spent during simulations. By knowing where the time goes, the hope is that researchers can streamline many small calculations. These small changes may eventually add up to large time savings. This work applies not only to simulations for the trigger system, but all ATLAS simulations.

"The high-level trigger is a continually evolving system," said Su. "It can make a huge difference to get the most out of our data, yet these types of software improvements don't have to be expensive."

Stay tuned! As the days leading up to the LHC turn-on dwindle, SLAC Today will continue its reports on SLAC's role. See yesterday's report on the ATLAS pixel detector here.

—Kelen Tuttle

SLAC Today, September 4, 2008