Handy Links

SLAC News Center

SLAC Today

- Subscribe

- Archives: Feb 2006-May 20, 2011

- Archives: May 23, 2011 and later

- Submit Feedback or Story Ideas

- About SLAC Today

SLAC News

Lab News

- Interactions

- Lightsources.org

- ILC NewsLine

- Int'l Science Grid This Week

- Fermilab Today

- Berkeley Lab News

- @brookhaven TODAY

- DOE Pulse

- CERN Courier

- DESY inForm

- US / LHC

SLAC Links

- Emergency

- Safety

- Policy Repository

- Site Entry Form

- Site Maps

- M & O Review

- Computing Status & Calendar

- SLAC Colloquium

- SLACspeak

- SLACspace

- SLAC Logo

- Café Menu

- Flea Market

- Web E-mail

- Marguerite Shuttle

- Discount Commuter Passes

-

Award Reporting Form

- SPIRES

- SciDoc

- Activity Groups

- Library

Stanford

Around the Bay

Ancient Secrets in Busted Dishes

Call it old-school outsourcing—more than 2,000 years ago, the Roman Empire exploited the labor of artisans in southern Gaul (modern-day France) to mass-produce a particular style of Italian pottery craved by the Roman populace. Now, synchrotron light is helping to detail the particulars of how this pottery was produced and how the method of production and quality of the ware reflects the rise and fall of the Roman Empire.

Call it old-school outsourcing—more than 2,000 years ago, the Roman Empire exploited the labor of artisans in southern Gaul (modern-day France) to mass-produce a particular style of Italian pottery craved by the Roman populace. Now, synchrotron light is helping to detail the particulars of how this pottery was produced and how the method of production and quality of the ware reflects the rise and fall of the Roman Empire.

"This pottery and how it is made—how the technology developed and declined—gives us clues about the end of the Roman Empire," says Philippe Sciau, one of two visiting researchers from the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in France.

The design of the pottery originated in Northern Italy, but as demand rose, factory ovens for mass production were built in southern Gaul. The Romans conscripted Gaulish workers to fire as many as 30,000 pieces at a time in these enormous ovens.

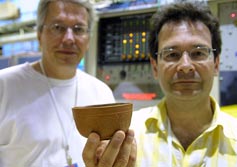

Together with fellow researcher Philippe Goudeau, Sciau visited the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) in early July to study fragments of the ancient pottery. These ancient shards have been found all over Europe, indicating the Romans distributed the pottery widely throughout the Empire. The fragments come from pots the size of a condiment dish, circumscribed with a delicate relief pattern and finished with a rusty pigmented coating called "slip."

The slip contains particles of iron, and it is the oxidation state of the iron that gives the pottery the deep red finish prized by the Romans. The chemistry involved in creating this type of finish requires extreme heat in very oxidizing conditions—a very difficult and energetically costly task in wood-fired ovens, where the primary products of combustion are reducing agents such as smoke, soot and other unburned hydrocarbons. Goudeau and Sciau are studying the oxidation state of iron and other elements in the slip, using microbeam (2 micron spot size) x-ray fluorescence and absorption techniques, for clues about the state of the technology of the ovens. Moreover, fragments of the original Italian pottery show slight differences from the Gaulish pieces; Goudeau and Sciau are investigating whether these differences were driven entirely by available raw materials, or if they reflect a process of maturation and transference of a technology suitable for relatively small domestic production to large-scale "global" manufacturing.

"This is one of the main questions," said Goudeau. "How did the pots change when production moved from Italy to France?"

Goudeau and Sciau owe their time at SSRL in part to an ongoing collaboration, under the guidance of Piero Pianetta (SSRL/Stanford), using x-ray and electron microbeam techniques to investigate cultural heritage materials, which is partially funded by the France–Stanford Development project. As a part of this collaboration SSRL scientist Zhi Liu investigated the Purple pigment found on the terra cotta warriors from the Qin dynasty (read a related SLAC Today story). Liu and Sam Webb aided the visiting researchers in collecting their x-ray absorption and fluorescence data.

—Brad Plummer, SLAC Today, July 25, 2007

Above photo: Phillipe Goudeau (left) and Phillipe Sciau visited SSRL in early July to study fragments of ancient pottery. Here, Sciau holds a replica of the clay pots.